Making a Small Lab Act Infinite: Acoustic Cloaking, Holography, and Cloning

If you have ever clapped in a small room or dropped a pebble in a bucket, you know the problem: waves bounce off the boundaries. In a real ocean, a quiet field, or outer space, waves can radiate away seemingly “to infinity.” In a lab, they hit walls and come right back. Those echoes contaminate measurements, shrink the space where we can trust the results, and make it hard to study how waves actually behave in the wild.

We decided not to fight that limitation with bigger rooms or thicker foam. Instead, we taught the walls to help. Our approach blends a physical experiment with a virtual world in real time. We call this Immersive Boundary Conditions (IBCs). Think of it as a portal: the lab stays small, but the waves inside it “believe” they are in an unbounded environment because the boundaries actively behave as if the outside extends forever. IBC let us switch off a lab’s walls, make objects acoustically invisible, project virtual objects into reality, and even clone the scattering fingerprint of anything we like—on demand and across a broad range of frequencies. For more details, see Centre for Immersive Wave Experimentation

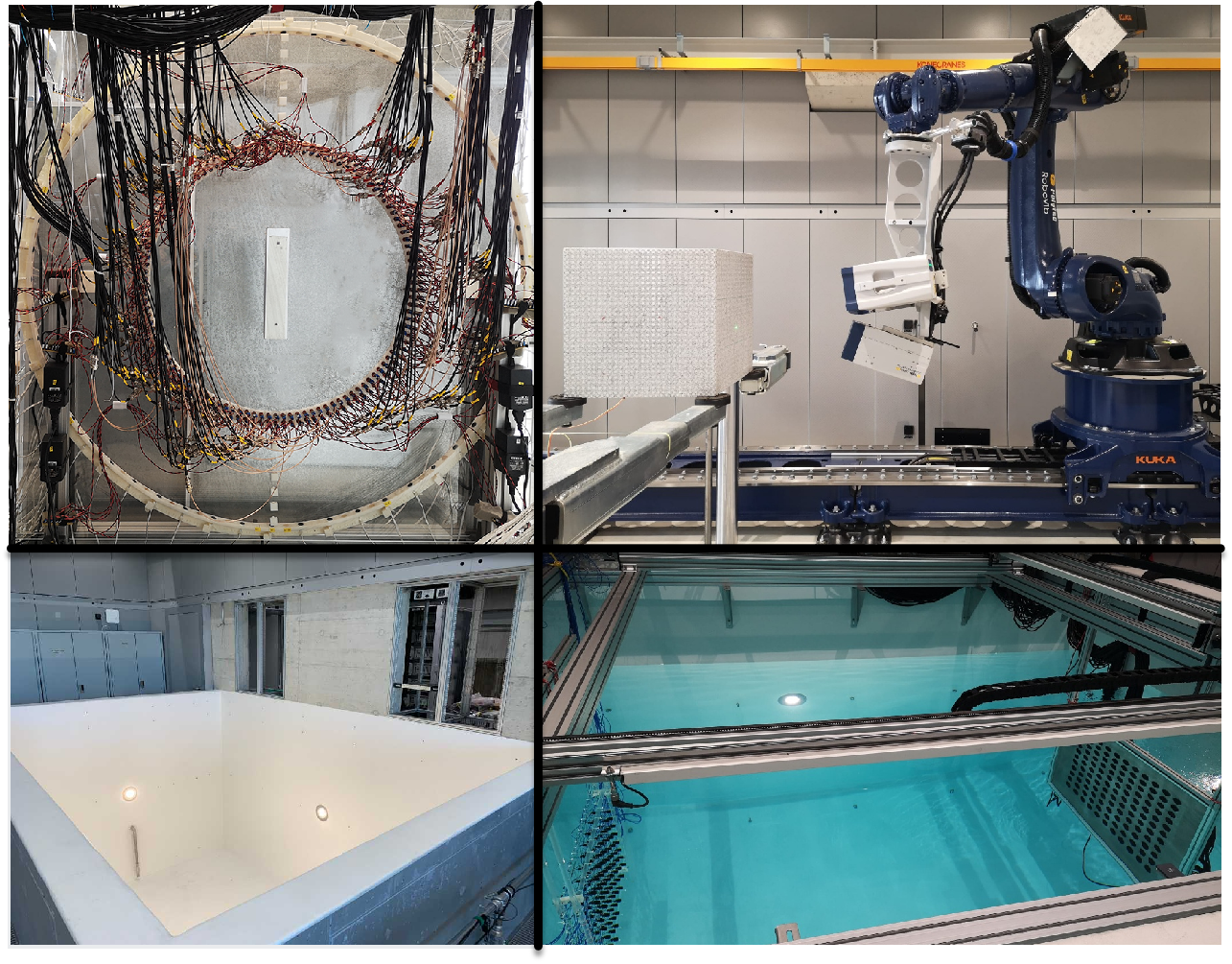

This is a versatile acoustic research facility where experiments at kHz frequencies are performed in compact, reflective spaces. For example, a 2D “sandwich” waveguide is used to simulate layered media and study broadband acoustic propagation, while a large water tank (measuring 3.1 × 4.5 × 2.7 m) serves as a quasi–3D environment for immersive experiments that bridge the frequency gap between laboratory and field scales. In addition, a state‐of‐the‐art LDV robot is employed to scan rock cubes, enabling precise elastic wave measurements at the surfaces of solid media. Together, these setups exemplify how ETH WaveLab uses Immersive Boundary Conditions (IBCs) and Multidimensional Deconvolution (MDD) to virtually remove lab boundaries, thereby canceling unwanted reflections, rendering objects invisible (cloaking), projecting virtual scatterers (holography), and even cloning full broadband scattering responses on demand.

1) The challenge: small labs, bouncing waves

In the wild—open water, the sky, or space—waves radiate away and their energy leaves the scene, but in tanks, rooms, and waveguides they ricochet off walls, polluting measurements and burying subtle effects like weak scattering or fine phase shifts. Anechoic chambers try to tame those echoes with foam wedges, yet their effectiveness collapses at low frequency because the wedge depth must scale with wavelength, making low‑kHz setups impractically large; in solid 3D volumes for full elastic P–S studies, operating around 1–20 kHz means wavelengths approach the sample size, so boundary energy can dominate the interior wavefield. Reduced‑size labs (kHz acoustics, plates, rooms, waveguides) thus suffer reflections that mask the very scattering we want to observe; passive absorbers are bulky and narrowband, while classic active cancellation degrades off‑axis and at higher frequencies. This is compounded by a scale gap: seismology and many field scenarios live below ~100 Hz, whereas conventional lab acoustics often push to hundreds of kHz or MHz to keep echoes at bay, making it hard to transfer insights—especially for frequency‑dependent phenomena like attenuation, dispersion, anisotropy, and nonlinearity that do not upscale reliably.

Size limitation causes wall-boundary reflections and restricts the natural propagation of waves.

Laboratories often suffer because their size is too small to simulate natural, non-boundary wave propagation. As shown, these boundary reflections strongly interfere with the interior experimental domain where scattering is being studied.

Related: Xun Li, Elastic immersive wave experimentation – Doctoral Thesis, ETH Zurich, 2022.

2) Immersive Boundary Conditions: Active wave energy cancellation

In size-limited laboratories, reflections from rigid boundaries often obscure the waves scattered by interior objects. One elegant solution is the deployment of active sources around the physical experimental domain. In an ideal implementation, the active boundary sources generate counter-waves that completely cancel the outgoing wavefield. As a result, the only waves visible in the experiment are those related to the interior scatterers, free from unwanted boundary effects. This clear separation is crucial for accurate measurement and analysis. Also, in this way, the experiment is virtually "immersed" into a much larger space where the propagation characteristics are as if no rigid boundaries were present. In effect, the physical wave propagation mirrors the behavior of waves in an idealized, boundary-free environment.

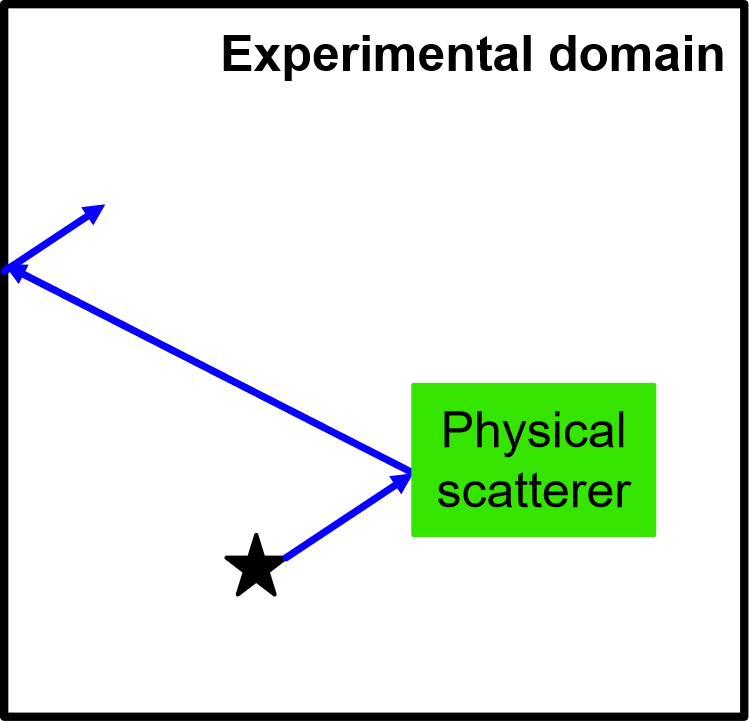

The concept of using active sources to cancel outgoing waves in a wave experiment.

The active sources can create a virtual environment by emitting waves designed not only to cancel naturally outgoing waves through carefully controlled emissions, but also to actively represent interactions between a physical experiment and an artificial virtual domain. In this configuration, the physical wave propagation experiment becomes seamlessly connected to an extended or virtual environment—the emitted waves embodying the desired properties of an unbounded, immersive domain while the propagating waves remain explicit in the physical realm.

By employing active sources to both cancel outgoing waves and emit tailored waves, we simulate an unbounded or extended experimental domain. This setup enables the representation of interactions between the physical and virtual environments, allowing for an accurate study of wave propagation and scattering phenomena as if the laboratory boundaries were non-existent.

Simulation movies of this approach strikingly illustrate that, with active cancellation, the laboratory’s confined physical space transforms into an immersive experimental domain. This environment faithfully replicates real-world scattering phenomena and supports broadband measurements without the distortions typically caused by reflections.

Waves propagating in the physical setup correspond exactly to the physical component of an expansive, virtual wave environment.

3) Immersive Boundary Conditions (IBCs): Real-time, broadband acoustic implementation

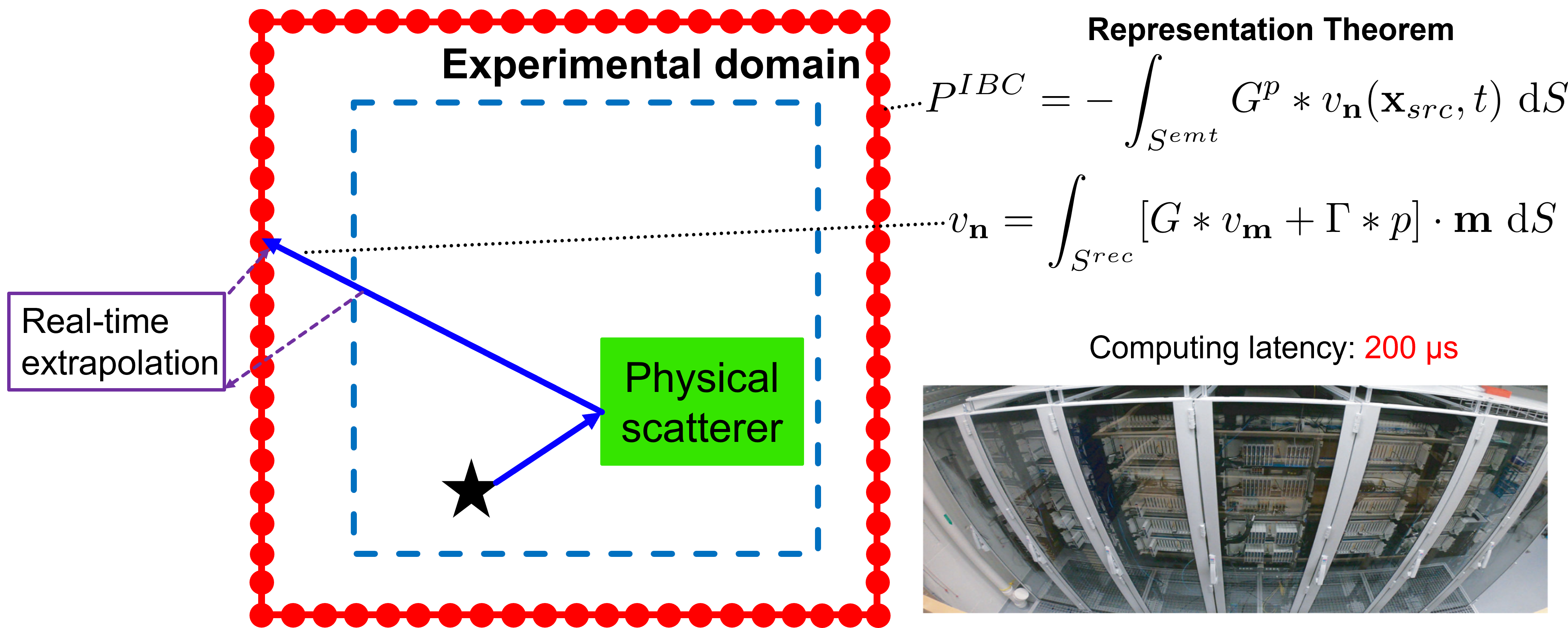

IBCs let us virtually replace what lies beyond a control surface by extrapolating measurements from an outer recording ring to an inner emitting ring in real time. In our implementation, pressure and particle velocity measured on a closed outer surface are used to predict the incident wave field on the inner boundary using representation theorems together with precomputed Green’s functions as “wave kernels” to extrapolate the field. This approach provides deterministic, broadband, and global control at low latency, independent of frequency or incident angle. With low-latency FPGAs (no more than 200 μs compute time), the extrapolated wave field is immediately re-injected into the lab so that waves cross seamlessly between the physical and virtual domains. This real-time prediction method cancels unwanted boundary reflections, enabling complex effects such as cloaking and holography without any prior knowledge of the incident wave.

Schematic showing the outer recording and inner emitting arrays and the real-time extrapolation loop.

Related: Becker et al., PRX, 2018.

4) Cloaking: Perfect invisibility at all angles without prior source knowledge

Think Harry Potter’s invisibility cloak: light bends around him and no one sees a thing. Doing that for light in open space is famously hard—an optical cloak would need to steer every color and every angle around an object and still deliver the wavefront to the observer “on time.” Passive materials run into causality and dispersion limits, so practical optical cloaks tend to be narrowband, angle/polarization‑limited, or confined to special geometries.

For sound, we take a different route: instead of hiding the object, we hide its acoustic signature. Using interior boundary control (IBC), an outer ring of microphones listens and a real‑time extrapolation predicts the wavefield at an inner ring of loudspeakers. Those speakers emit a secondary field that cancels the object’s scattering—including multipath from the lab boundaries—without any prior model of the incident sound. Even moving or unknown sources can be cloaked.

A primary source generates the incident field; control loudspeakers add a secondary field that suppresses the object’s scattering. Control inputs are computed in real time by forward wavefield extrapolation from microphone measurements.

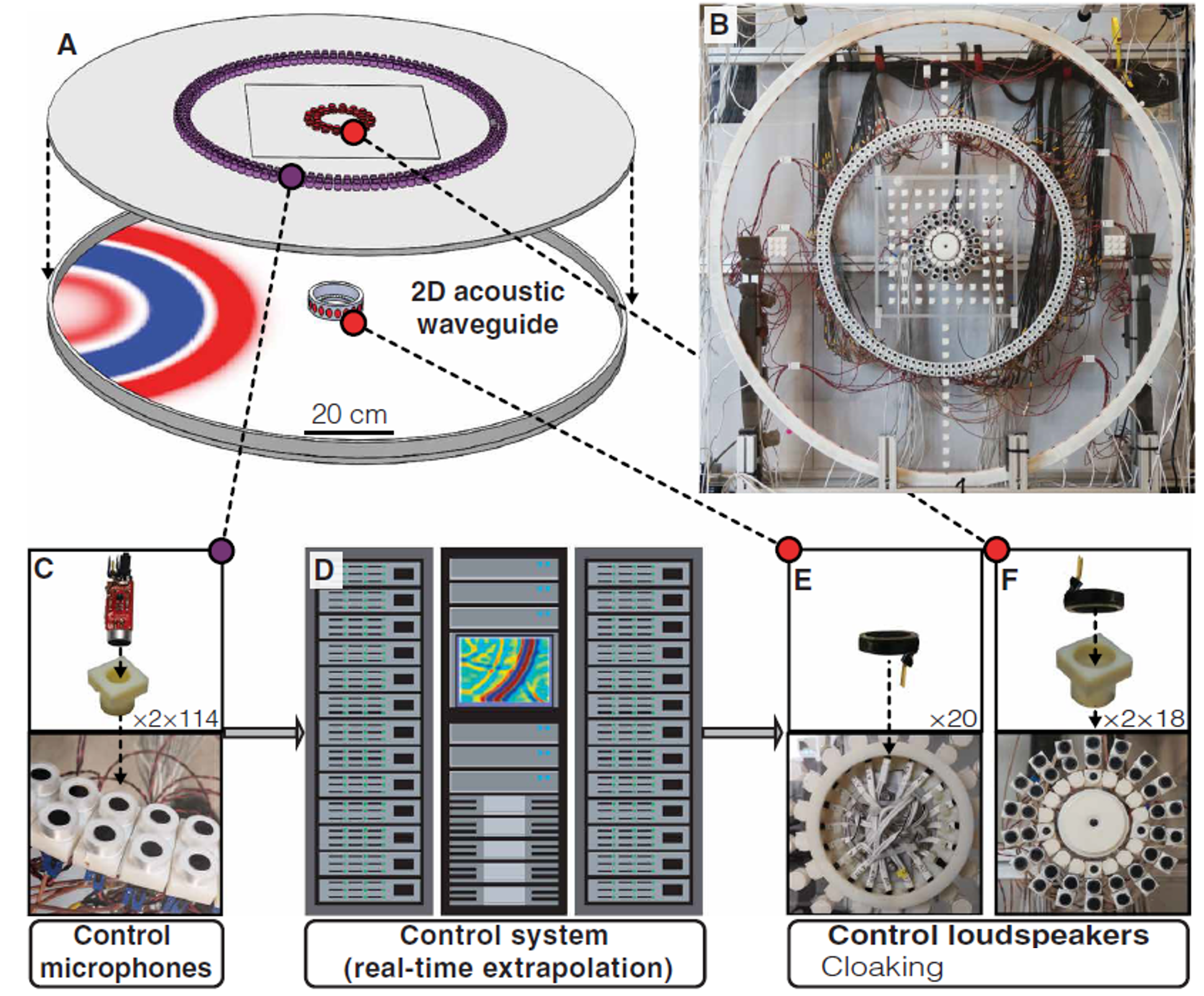

(A) schematic and (B) photograph. Two circular arrays of 114 microphones each record the pressure field (C). An FPGA-based low-latency computational and control unit. (D) performs real-time extrapolation to drive the control loudspeakers (E, F).

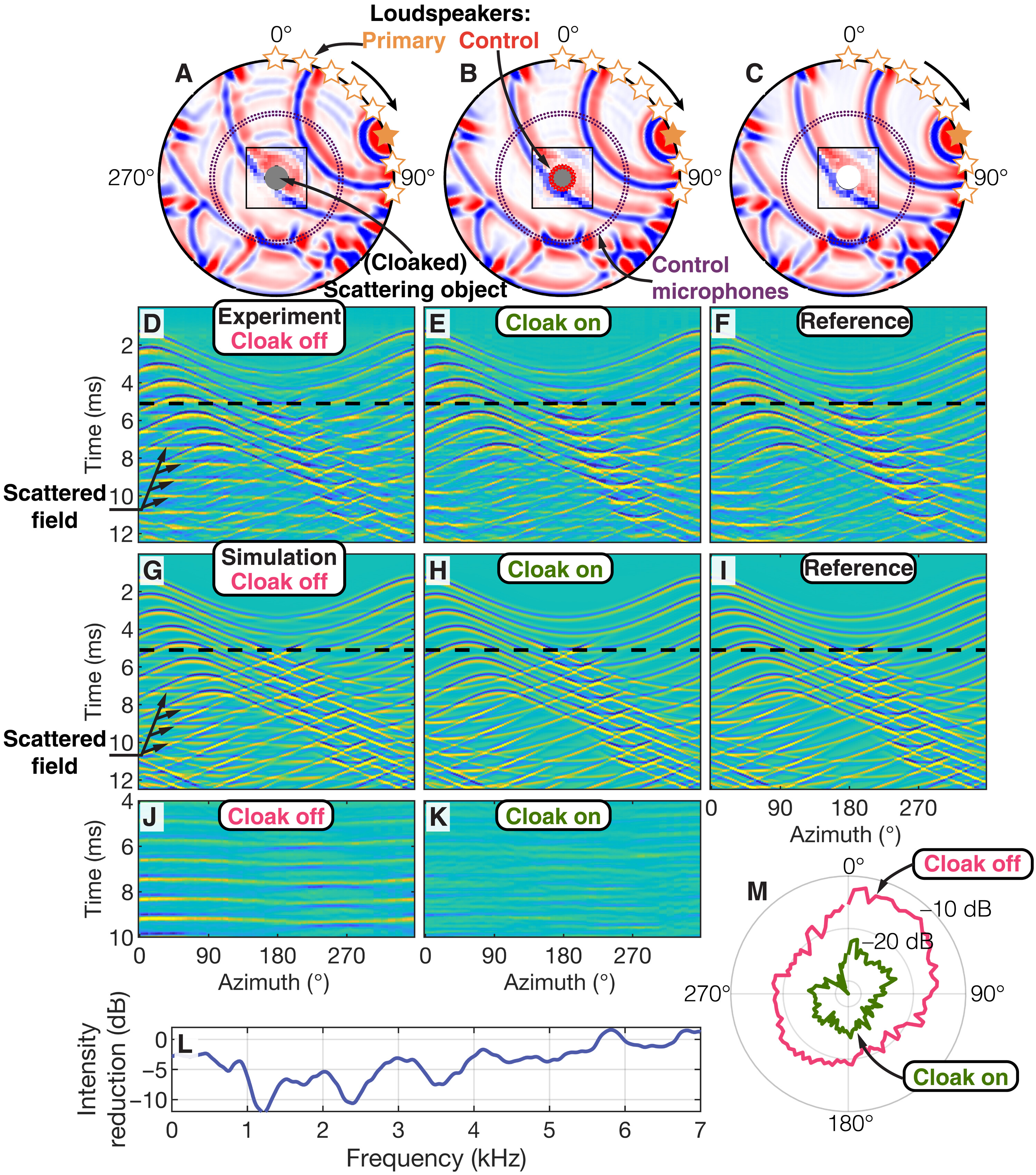

What does “invisible” look like in practice? We cloaked a quasi‑rigid circular scatterer (diameter 12.6 cm) inside a 2D waveguide by surrounding it with 20 control loudspeakers. A moving broadband primary field was synthesized by eight sources along a 96° arc. With the cloak off, both back‑ and forward‑scattering are visible; with the cloak on, the measured total field matches the “no‑object” reference—even at later times when wall echoes dominate. Finite‑element simulations closely reproduce the measurements. Across ~3.5 octaves (up to ~8.7 kHz), the mean scattered intensity at the outer array is reduced by about −8.4 dB and the angular scattering pattern is uniformly suppressed, demonstrating all‑angle, source‑agnostic cloaking.

(A–C) Experimental setup and snapshots; (D–F) measured fields at the outer microphone ring; (G–I) simulations of the same; (J–K) scattered fields without/with cloak; (L) reduction in scattered acoustic intensity versus frequency; (M) angular distribution of scattered intensity.

Examples adapted from Becker et al., Science Advances, 2021.

5) Holography: Cheat an observer with virtual imprints

Picture the classic sci‑fi hologram: a lifelike person appears in front of you to talk, even though they’re far away. The trick is that your eyes receive the exact wavefronts they would have seen if that person were really there. Acoustic holography does the same for sound. We make microphones and loudspeakers conspire so an observer hears precisely the scattered field a chosen object would produce—even when that object isn’t present. By predicting, in real time, the wavefield on a sound‑transparent inner surface and driving collocated monopole+dipole emission (two close loudspeaker rings), we “imprint” a virtual object into the lab. To microphones (and your ears), the illusion is indistinguishable from the real scatterer. Note that we use the same real-time extrapolation as for cloaking, but now to recreate the object’s scattered field rather than cancel it.

A primary source emits an initial wavefield (C), and active control sources create a hologram of an object that is not physically present (D). Control inputs are obtained by real‑time forward extrapolation from control sensor measurements.

(A) Experimental setup and snapshots at 2.5 ms and corresponding simulations. (B) Reference with a physical object inside the waveguide. (C) Active hologram: control loudspeakers enabled, no physical object. (D) Angular distribution of scattered intensity for a physical (E) and virtual (F) scatterer.

Examples adapted from Becker et al., Science Advances, 2021.

See also: van Manen et al., JASA, 2015 (original theory); Börsing et al., Phys. Rev. Applied, 2019 (1D demonstration).

6) Acoustic Cloning: A Digital Twin Enabling Scatters Like the Real Object

Acoustic cloning is a powerful, two‑step strategy that ultimately creates a “digital twin” of a real scatterer—that is, a non‑physical replica that reproduces the same acoustic scattering characteristics as the original object. In our system, the fundamental idea is to record the true scattering response of an object embedded in a well‑defined experimental environment and then use that retrieved information to “play back” the object’s influence on any arbitrary incident wavefield. This entire process unfolds in two primary steps:

Step 1: Acquiring the Scatterer’s Green’s Functions Using MDD

The first stage of acoustic cloning involves illuminating the real scatterer with controlled broadband signals. During this illumination, wavefields are recorded on a closed, sound‑transparent receiver aperture surrounding the scatterer. By applying the method of multidimensional deconvolution (MDD), the experimental data are post‑processed to extract the scatterer’s full set of Green’s functions. These functions characterize how the acoustic wavefield propagates from the sources through the medium and scatters off the object. Crucially, the MDD approach removes any extraneous contributions—such as multiple reflections and boundary effects—that would otherwise “pollute” the clean scattering signature of the object.

By eliminating the boundary‑induced reverberations, the resulting Green’s functions represent the object’s response under ideal radiation conditions. In other words, we retrieve the “pure” scattering characteristics as if the object were in an unbounded space.

Once the raw data have been decomposed into their incident and outgoing components (a key process in MDD), a set of coupled Fredholm integral equations is formulated. Solving these equations in a least‑squares sense enables us to reconstruct the Green’s functions that reveal the object’s scattering behavior.

What Does This Mean Practically?

No prior knowledge of the object’s material properties, geometry, or source signature is required. Every detail is captured from the measurement data, making the approach remarkably general and robust even in reverberant laboratory environments.

In summary, after illuminating the scatterer and applying MDD, we obtain a set of Green’s functions that isolate and capture the object’s scattering response. For example, by subtracting the homogeneous (direct wave) component, only the contributions from the scatterer remain.

Step 2: Reconstructing the Scatterer with Real‑Time Holography

With the scatterer’s Green’s functions in hand, the next step is to recreate the object’s acoustic imprint within the lab—even after the physical object has been removed. This is achieved using a holographic reconstruction process:

- Deactivate the Object: The physical scatterer is removed from the experimental domain.

- Replay Green’s Functions: The previously retrieved Green’s functions are used as signal templates to drive an array of transducers on the inner ring (SI). These transducers emit time‑varying monopole and dipole signals derived from the Green’s functions.

The resulting wavefield, excited by these precisely calibrated signals, reproduces all scattering phenomena—including multiple interactions between the incident wave and the scatterer’s numerical imprint—exactly as if the original object were still in place.

A Few Notable Features of the Holographic Clone:

• Broadband Robustness: The hologram responds correctly for any incident broadband wavefield.

• Versatility: Whether the original scatterer is circular, square, or a complex cross, the holographic reconstruction faithfully reproduces its scattering features.

• Real‑Time Reproduction: The reconstruction occurs with low latency; the echo and interference patterns build up in real time.

Augmenting the Digital Twin: Beyond Cloning

An especially exciting aspect of this approach is that the twin is defined digitally. Once the scatterer’s Green’s functions have been retrieved, they can be manipulated arbitrarily. For instance, you can:

- Rotate or Translate the Clone: Configure different spatial arrangements without physically modifying the original object.

- Scale Amplitudes: Introduce directional gain to alter the amplitude of scattering in specific directions.

- Modify Impedance or Transparency: Create “acoustic cyborgs” that interact with real wavefields while exhibiting non‑physical (or enhanced) behaviors.

These digital modifications can be made prior to playback through the holographic emitter. This opens up applications in:

- Enhanced metamaterial designs, where unit cells can be cloned and arranged without the challenges of physical manufacturing.

- Virtual acoustic models, allowing simulation of an object’s response in various environments or configurations—thereby enabling rapid prototyping and testing.

Wandering Thoughts

Acoustic cloning feels a bit like moving from making models of the world to making models that act back on the world. We’re not copying atoms or materials; we’re copying how an object behaves when sound meets it—its scattering fingerprint—and then letting that behavior live on without the object. In that sense, the “clone” is less a replica and more a portable skill: a learned interaction you can carry to new places, switch on and off, or even bend to your will.

Why does this matter? Because interaction is often what we care about most. Acoustic cloning captures the full give-and-take between a wavefield and an object, across angles, frequencies, and multiple reflections. That changes how we prototype and experiment. Instead of machining many variants of a metamaterial, you clone the unit cell once and iterate digitally. Instead of hunting for anechoic spaces, you bring your own “infinite” lab with you. Instead of waiting for large simulations, you measure, learn, and replay—on demand.

The ripple effects extend beyond research. Imagine:

- Design at the speed of thought: Try, measure, clone, tweak—repeat. Turn days of fabrication into minutes of iteration.

- Acoustic heritage and education: Preserve the “sound” of instruments, halls, or artifacts and let students interact with them anywhere.

- Personalized spaces: Car cabins, classrooms, and headsets that remix their acoustic behavior in real time for comfort, clarity, or immersion.

- Metamaterials, demystified: Clone a unit cell, tile it virtually, and explore nonphysical variants (gain, custom directivity) before ever building.

Of course, power invites responsibility. If we can project acoustic “truths” into a room, we should mark what’s real and what’s rendered. Standards for safe output levels, disclosure in public spaces, and reproducible reporting will help keep the tech trustworthy. And we should keep sight of the limits: a clone is only as good as the bandwidth and geometry it learned from.

Personally, what excites me most is how tangible this feels. It’s not just a simulation on a screen; it’s physics you can stand inside. The jump from measuring a thing to becoming it—acoustically—changes how we ask questions. We can now ask “What if this object were rotated, softer, or directional?” and get the answer back from the lab in real time. That’s a different kind of conversation with nature—and one I suspect we’re only beginning to have.

Examples adapted from Müller, J., Becker, T. S., Li, X., et al., Phys. Rev. Applied. (2023)

For further reading into the theory and implementation of MDD , please refer to the MDD work.

7) Applications: Where Immersive Wave Experiments Make a Difference

What excites me about immersive wave experimentation is how it transforms a cluttered, small lab into an imaginative playground—a place where ideas usually confined to simulations take on life. Imagine switching off walls, dropping virtual media into the mix, and crafting physical/virtual hybrids that behave like materials we haven’t even built yet. In our lab, we talk about these experiments with energy and enthusiasm, and here are just a few examples of where this technology makes waves—literally and figuratively:

- Mixing Real and Virtual Wave Scattering. Prototype complex samples by combining a tangible physical core with a flexible virtual surround. Measure once, then remix shapes, impedances, and arrangements digitally—no need for re-machining after every tweak.

- Virtually Created Media and Metamaterials. Build phononic crystals and metamaterials in software; let your lab “feel” them in real time. Explore phenomena like gain media or parity–time (PT) symmetric responses that would be impossible to achieve with traditional passive materials.

- Independent Car Audio. Imagine creating multiple immersive zones—one per passenger—by surrounding each listener with compact arrays that couple to their own virtual acoustic space. The result? A personalized soundscape delivered without overwhelming the cabin.

- VR-Room Acoustics for Learning and Play. Step into “impossible” rooms that morph from the echo of a cathedral to the silence of an anechoic box. Students and audiences can walk through these dynamic environments while the same wavefield is measured in real time.

- Hybrid Metamaterials and Phononic Crystals. Embrace the best of both worlds: keep one physical unit cell while virtually tiling the surrounding lattice. This fusion lets you experiment with sweeping changes in geometry, bias, and non‑physical parameters (like gain, loss, or asymmetry) between measurements—without having to rebuild your setup.

- Nonlinear, Time‑Varying Media & PT Symmetry. Inject controlled nonlinearity or time modulation directly into your numerical models, then tether them to the real wavefield. Mix a virtual gain medium with a physical lossy element to craft direction‑dependent transmission and absorption effects that passive samples simply can’t sustain.

- Digital Twins and Cloning. Capture a scatterer’s Green’s functions and replay them holographically. In doing so, you can “clone” the object on demand—rotating it, moving it, or digitally modifying its impedance at the drop of a hat.

- Low‑Frequency, Broadband Rigs and Collocated Apertures. Future-ready modular 3D arrays can span entire rooms (≈2.7 × 3.1 × 4.5 m) and dive deeper into lower frequency regimes without needing bulky absorbers. By collocating emit/record surfaces, we can suppress higher‑order coupling, making first‑order Green’s components the stars of the show—thanks to low‑latency control.

- Open Recipes for Safety and Reproducibility. The idea is to eventually share kernels, calibration sets, and level‑safe presets so that others can reproduce—and responsibly deploy—immersive experiments. In this way, the lab isn’t just editing waves; it’s editing the rules of the game.

Beyond these immediate applications, immersive wave experimentation opens doors to entirely new realms of physics and wave control strategies. By blending physical and virtual worlds, our lab becomes more than a measuring instrument—it evolves into a dynamic canvas on which we sculpt the flow of energy and matter.

There’s also a deeper scientific edge to this work. Elastic immersive wave experimentation unlocks a low‑frequency window (≈1–20 kHz in solids) that conventional small labs struggle to explore. In this regime, wavelengths are comparable to sample sizes, providing an ideal testbed for homogenization theory, scale‑bridging ideas, and advanced techniques like time reversal and virtual source methods. This is where the lab not only pushes the envelope of wave manipulation but also pioneers potential breakthroughs in seismic imaging and non‑destructive testing.

Graph adapted from: Elastic Immersive Wave Experimentation (ETH Zurich, 2022).

In short, by merging the tangible with the virtual, we are not just capturing wave phenomena—we are reinventing them. Every experiment becomes a leap into uncharted territory, where physics, engineering, and creativity converge to redefine what’s possible.

References

Li, X. (2022). Elastic immersive wave experimentation [Doctoral thesis, ETH Zurich]. DOI: 10.3929/ethz-b-000573091

Li, X., Becker, T., Ravasi, M., Robertsson, J., & van Manen, D.-J. (2021). Closed-aperture unbounded acoustics experimentation using multidimensional deconvolution. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 149(3), 1813–1828. DOI: 10.1121/10.0003706

Becker, T. S., van Manen, D.-J., Haag, T., Bärlocher, C., Li, X., Börsing, N., Curtis, A., Serra‑Garcia, M., & Robertsson, J. O. A. (2021). Broadband acoustic invisibility and illusions. Science Advances, 7(37), eabi9627. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abi9627

Becker, T. S., van Manen, D.-J., Donahue, C. M., Bärlocher, C., Börsing, N., Broggini, F., Haag, T., Robertsson, J. O. A., Schmidt, D. R., Greenhalgh, S. A., & Blum, T. E. (2018). Immersive wave propagation experimentation: Physical implementation and one‑dimensional acoustic results. Physical Review X, 8(3), 031011. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevX.8.031011

Müller, J., Becker, T. S., Li, X., Aichele, J., Serra‑Garcia, M., Robertsson, J. O. A., & van Manen, D.-J. (2023). Acoustic cloning: Creating digital twins of acoustic scatterers in immersive wave experiments. Physical Review Applied, 20(6), 064014. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.20.064014